March 18, 2024

Dear Friends,

Recently, I was interviewed by Isabelle Boemeke, a Brazilian fashion model known also as the world’s first nuclear influencer, I_sodope … that weird and sassy character on Twitter/X who made nuclear energy cool among the younger generations. The interview was motivated by a book she is writing on the subject of nuclear energy that will be titled ‘Rad Future’, to be published by Penguin Random on Earth Day 2025.

(By the way, did you catch that name … i_sodope? That’s a play on the word ‘isotope’ while subtly messaging how dope it really is. If you don’t get it, nevermind!)

As Isabelle tells it, she began her explorations into the subject of civilian nuclear energy after reading a Tweet of mine. Proud? Who, me? After a couple of years of I_sodope and her catchy, clever videos (here’s an example) …

… Isabelle was invited to present her work on the TED stage. You can check out her beautiful 2022 TED talk right here, especially the first minute! :-)

Caption: Isabelle Boemeke makes her case for civilian nuclear power on the TED stage. She received a standing ovation. (Credit: TED)

And here is a picture of Isabelle and me on a tour of the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant near San Luis Obispo, USA, December 2021 …

Caption: Isabelle Boemeke and I at the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant, San Luis Obispo County, December 2021. (Credit: Carolyn Porco)

… when she was in town to lead a rally in downtown SLO to keep Diablo Canyon open.

Caption: That’s me speaking at the Save Diablo Canyon rally in downtown San Luis Obispo, December, 2021. Isabelle is at my side. (Credit: Unknown)

Operations of Diablo Canyon NPP have since, thankfully, been extended at least until 2030. There was lots of celebrating over that!

Caption: Image of Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant on the California Central Coast. Even the wildlife celebrated its extension into the future. (Credit: John Lindsey)

Back to the interview … I thought you all might be interested in what I had to say in response to Isabelle’s questions so I’ve posted the interview below. I hope it’s obvious that I wouldn’t mind one bit, and would really appreciate it, if you encouraged your friends, family, colleagues, and anyone you think might also be interested, to subscribe to this newsletter. The more, the merrier. FInally, if you are so moved, leave your own responses and comments at the bottom of the page. I’d love to read them.

Enjoy!

Carolyn Porco

Carolyn, you lived through the birth of the anti-nuclear movement in the US and attended anti-proliferation protests. How was that experience?

I can't recall civilian nuclear power appearing on my radar screen, either during my school years or even into my career. I was too consumed with my education and later my professional life to take much notice of political things, like the anti-nuclear movement.

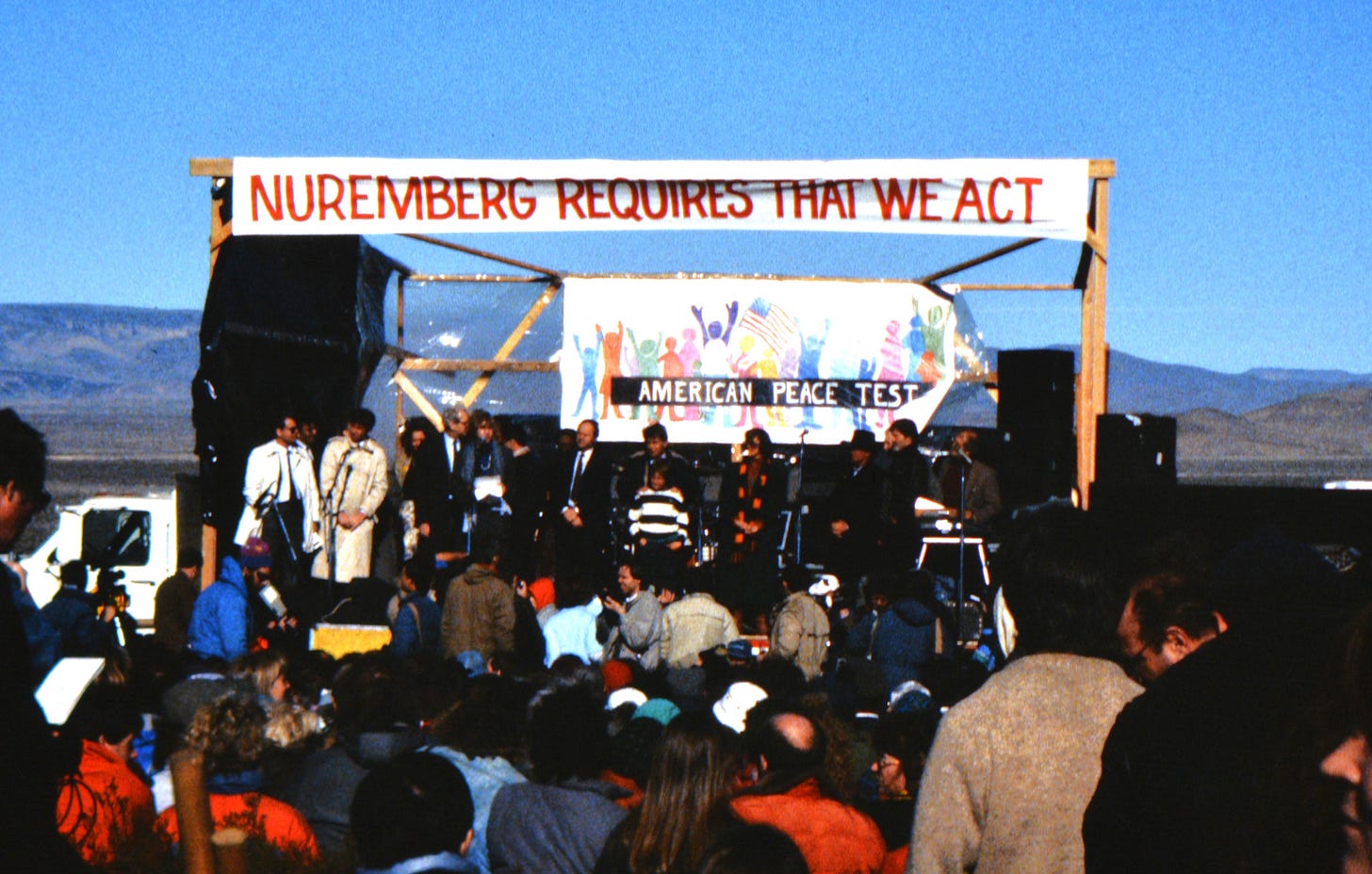

But I did attend a 1987 protest at which I knew Carl Sagan would be speaking. Carl, who was a colleague, friend, and mentor of mine, had been against nuclear weapons proliferation since his student years at the University of Chicago where the first nuclear reactor had been built and where he first became aware of the seriousness of nuclear proliferation. And from that grew his crusade later in life against nuclear weapons.

I was a research associate in the Lunar and Planetary Lab at the University of Arizona in Tucson in the 1980s. When I heard that Carl was going to be speaking at the Nevada Test Site, near Las Vegas, on February 5, 1987, I joined a caravan of UofA students, post-docs and others headed for Nevada to protest along with Carl. There were 2000 demonstrators. Carl was one of about 400 people …

Caption: Images from the February 5, 1987 protest against nuclear weapons proliferation at the Nevada Test Site near Las Vegas. Sagan is speaking in the bottom-most image. (Credit: Carolyn Porco)

… who were arrested trying to enter the site. He was putting himself on the line to draw attention to the need to stop the proliferation of nuclear weapons.

The experience was for me a good introduction into the effort that is often required if you want to bring about policy changes at the highest levels. I began taking mental notes.

How did you come to be an advocate of nuclear energy?

In January 2011, during a visit to Pasadena, California for a Cassini meeting at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the organization that managed the Cassini project for NASA, I learned of a lecture to be given at Caltech by a renowned, highly accomplished astrophysicist whose reputation I knew well. His name was Frank Shu, and along with my thesis advisor and my advisor’s collaborator, was one of the architects of the scientific discipline in which I worked for my dissertation … the study of planetary rings. He was gifted, one of only nine distinguished University Professors in the University of California system, a former president of Taiwan’s top research university, and a recipient of the Shaw Prize, considered the Nobel Prize of the East. You don't pass up the chance to hear someone like that speak.

I went to his lecture and was pleasantly surprised to learn that he was now using his intellect and time trying to figure out what to do about the climate crisis. His lecture was on nuclear power. He was professionally an expert in the structure, composition, and behavior of stars so he understood radioactivity and the structure of the atomic nucleus at a very deep level. He was pushing a reactor design that he felt was superior to the common designs that had been in use for decades. His design used molten salt as a coolant and fuel and radioactive thorium as a breeder fuel. In such a reactor, if there's a problem and the fuel gets too hot, it expands, the density goes down and the reactions cease until it cools. In other words, meltdowns are impossible because the fuel is already molten. One statement Frank made that day really stuck with me: 'Such a reactor behaves like the Sun.' I thought that was brilliant.

Frank’s lecture was such an eye-opener and his proposal sounded so promising that I became very interested in the subject and started studying up on it. I eventually became convinced that nuclear power is the best source of energy there is and, at large scale, better than wind, better than solar. I decided that the most effective way I could make a contribution to solving the climate crisis was to advertise my own support for it on social media. That's when I started Tweeting about it. One of those Tweets is the one you saw, and the rest is history!

Why do you think so many people conflated nuclear weapons and nuclear energy?

Can you think of an industry that had a worse rollout than nuclear?! The first demonstration of the kind of energy that could come out of the nucleus of an atom were events of unprecedented, horrific, grotesque mass destruction. (I'm of course referring to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.) Even if it's simply being a TV witness, that’s the kind of experience that never leaves you and is not the kind of first impression you would want to make on others if you're hoping to convince them that something can be used for good. And to top it off, you tell them, 'Oh, and we want to put this in your backyard'. Not a sensible strategy. But that was indeed the backdrop to the first suggestion of civilian nuclear power. It's been a long, steep uphill battle for nuclear power plants ever since.

In addition, the technical distinction between bombs and nuclear reactors is lost on most of the listening public. I think fear prevents them from absorbing the notion that the amount and kind of nuclear material and what is done with it are the core distinctions between bombs and reactors.

Most people, I suspect, have the same ignorance about the way their automobiles work. You don't need to understand the mechanics of a car to drive one, so we happily, thoughtlessly get in and out of them every day. But people have also never seen an automobile used to kill 140,000 people in one go! If we had, maybe we'd still be using horse-drawn carriages.

I'm seeing the current surge, especially among the young, in the acceptance of nuclear power as the result of several facts. First, we have many reactors around the world that have been up and running for decades with only 2 really notable accidents ... Chernobyl and Fukushima. It's been 79 years since the end of WWII and we've never in that time seen a nuclear bomb used in warfare. So, young people have neither the memory nor the fear of a nuclear bomb detonation, nor do they have the long-standing, entrenched, knee-jerk, negative reaction that their elders have. There is an old expression, 'Science progresses one funeral at a time.' I think in this case, the appropriate expression might be, 'Human societies progress one generation of funerals at a time'. Fears like this take a long time to uproot.

Did you ever have the same issue?

No. I was a physics major and so I was familiar with the basic concepts like critical mass density.

You were a part of the Cassini mission, which used a nuclear battery. You’ve mentioned that people were very apprehensive about that. What were some common misconceptions they had about the dangers of Cassini?

Some months before the Cassini launch on October 15, 1997, I was chosen by the public affairs office at JPL to be one of the spokespersons for the Cassini project on the matter of the radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTG) that Cassini carried for power. The radioactive material in them is plutonium-238 which, by the way, is not fissile and cannot sustain a chain reaction as in a bomb. In an RTG, the plutonium is bonded with oxygen in the form of a ceramic, PuO2 or plutonium dioxide. The natural radioactive decay of the plutonium heats the ceramic to tremendous temperatures and that heat is converted into electricity. Cassini would carry the largest amount of PuO2 ever taken into space.

At the time of launch, a movement grew, headed by Michio Kaku, a well-known physics professor at City College of New York, opposing the launch because of the dangers they saw. They worried that a rocket explosion at launch would spread radioactive plutonium-dioxide dust all over southern Florida, and that an accidental Earth atmospheric re-entry and incineration of Cassini during the 1999 Earth flyby would spread enough material around the world to have dire global consequences. 'The most toxic substance known to man' was the tagline used at the time to describe plutonium. That, in fact, was a statement made by Ralph Nader in 1975 in a debate about nuclear power, in which he also said, 'One pound of Plutonium could kill every human being on Earth.' Both statements were repeated regarding Cassini.

Neither statement is true in the real world. Plutonium is not the most toxic substance by far; Botulinum toxin apparently is. Also, to kill every human on Earth, a bit of PuO2 dust would have to be specially delivered into the lungs of every human on Earth and would have to remain there for a while and not be expelled by coughing. That would not have been at all likely during Cassini's flyby of the Earth.

I participated in interviews and debates and I wrote an OpEd to explain the facts. It's a never-ending job and responsibility, really, to educate the public. We who have worked with scientific concepts all our lives can easily forget how complex and confusing things can appear to the non-scientist. But we must continue with it, in this case especially, because the very health of the planet and the creatures living on it are at stake.

You have been a vocal supporter of nuclear energy throughout your career. Have you ever faced criticism for this from within the scientific community?

Well, actually only for the last 13 years have I been vocal about it. In that time, sure, I’ve gotten into arguments on social media about it and some of those people, I suppose, have been scientists. But no one in my community of scientists has been critical, at least as far as I know.

You worked very closely with Carl Sagan, who was a very vocal anti-nuclear weapons activist. Did he ever share his views on nuclear energy with you?

No, we never spoke about it and I never heard Carl say anything in person or otherwise about nuclear reactors until just recently, in the last few years, when this video began circulating on social media. It is Sagan's 1985 Congressional testimony on climate change.

At timestamp 12:35, he asks ‘What can be done about it?’ He answers i) fewer government subsidies [to the oil industry] and ii) alternative sources. He mentions solar power and then "safe fission power plants, which are in principle possible, and on a longer timescale the prospect of fusion power. Fission and fusion power plants vent no infrared active gases"

This was said before the Chernobyl accident which occurred in April 1986. I know he spoke against nuclear weapons after the Chernobyl accident but I don't know if he went so far as to unequivocally oppose nuclear reactors after the accident. Carl was a very well-reasoned individual. He would surely see the benefit of safe nuclear power and would, like myself, see the distinction between the Chernobyl accident — a reactor of poor design operated by poorly trained operators — and what we build and how we operate in the US.

Do you think accidents like Chernobyl are a warning to us that we should consider nuclear energy too dangerous and reject it?

The accident at Chernobyl has no bearing on our civilian nuclear activities here in the US. The Chernobyl reactors, which utilized a faulty design unique to the Eastern Bloc of the Soviet Union, went on line in the early 1970s. That means they were being built during the 1960s. At that time, the US was in a race with the Soviet Union to get to the Moon. As we all know, the US won handily and for a very good reason. When Gorbachev became the Soviet leader in 1985 and the openness of glasnost allowed freer exchange of information between the US and the Soviet Union, we learned that the Russians never stood a chance against us in getting to the Moon. Our engineering standards, technological knowledge and safety culture were superior to theirs. And the same applies to the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. So, in my mind, it is a false equivalence to point to the Chernobyl accident and say that nuclear power of all kinds, therefore, is dangerous everywhere. Do we point to electrical power and say, when someone is electrocuted or a transformer on the electrical grid explodes and starts a deadly fire, that we must quit using electricity? Of course not. Instead, we make efforts to make it safer. The record shows, nuclear power can be made very safe.

How do you think public opinion on using nuclear reactors for electricity has changed?

It's getting very much better because we've seen for decades now the proof of concept all over the world. Many years have passed since the 1970s and we have seen the superiority of nuclear power — its lack of greenhouse gases, its persistence and dispatchability — over the usual renewable sources during that time. As I stated above, the younger generations look at all the evidence without prejudice. The older generations are still saddled with those old fears and ideas. I'm hopeful youth will prevail.

What gives you hope for a nuclear-powered future?

The internet and social media have each changed a great many things, for good and bad, but the best in my mind is the access to information. As a result, I think now people in general, myself included, are very much more aware of the detrimental changes human civilization is bringing to the climate and the biosphere, and many of us want to know what's going to be done about it, and what we can do to stop it. For the younger generations, who have most of their lives before them, it is a matter of acute significance. If we don’t set this ship right, it is they and their progeny who will suffer. The future is theirs and they will make it so.

Nuclear Power to the People https://open.substack.com/pub/carolynporco/p/nuclear-power-to-the-people?r=25sxvl&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=email

Carolyn Porco, the NASA scientist responsible for the beautiful images of Saturn’s rings, whom I have met and very strongly respect, writes brilliantly in support of safe and non-polluting nuclear power. I agree with every word!

Thank you for using your influence on behalf of civilian nuclear energy. The first thing we need to do is to stop the irrationality of shutting down perfectly fine NPPs, and the second thing is to build more of them.