March 27, 2024

Dear Friends,

On this day, 20 years ago and a billion miles from here, the Cassini spacecraft had reached a point in its approach to Saturn where the planet and its rings just exactly filled the field of view of our highest resolution telescope, the narrow angle camera (NAC). From that point onward, imaging the rings end-to-end with the NAC would require a mosaic of multiple images. So, I thought back then that it would be nice to mark this special ‘last eyeful’ turning point with the release to the public of a color image.

Producing natural color was not, on any previous planetary mission, ‘the thing’ that I made it on Cassini. Here’s the backstory.

Between the years 1979 and 1989, the Voyager spacecraft paid visit to each of the giant planets in the outer solar system … Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. And on each morning of the week straddling each planetary encounter, there would be a news briefing to report to the gathered press corps and to the world, the scientific findings of the previous 24 hours and our interpretations of them. It was always a mad, chaotic rush, often with scientists and JPL graphics personnel pulling all-nighters, to get the materials ready for presentation, followed early the next morning by a pre-press-briefing review and selection of the most presentation-worthy items.

Caption: Voyager Imaging Team leader Brad Smith, myself, and personnel from both the JPL public affairs office and image processing lab selecting the best images for presentation at a Neptune encounter press briefing, August 1989.

The era had not yet arrived when digital files could be readily shipped from one person’s computer to another in the next room, and images could be routinely attached to emails and shipped across the country or posted on a social media platform. Whatever processing was needed to make the Voyager raw images look good – either contrast enhanced, cleaned of noise, mosaicked together, and/or turned into color – it all had to happen very quickly for the next morning’s press conference.

Given the urgency, no one was especially concerned with making colors accurate. It had never in the history of the planetary space program been a concern and I’m pretty sure the thought never occurred to anyone. All processing was done simply to make some scientific point as clear as possible to the press the following morning.

And when finally the encounter was over and everyone went home, if the press or even we Voyager scientists later wanted images from JPL, they were shipped out as either hard-copy or as a package of slides.

But there was one member of the press corps who took the Voyager imaging team to task at every encounter for not making the effort to present the images in natural color: ie, the color that we would see if we were there. His name was Andrew Young, and he was also an amateur astronomer and therefore familiar with what planetary objects, especially colorful ones like Jupiter and Saturn, should look like. I think the older team members were irritated with his criticisms. But I happened to agree with him.

So when the day eventually came that I learned that I had been chosen as the leader of the imaging team on the Cassini mission, I began constructing my bucket list of goals and wishes for our forthcoming adventure. One was to re-do the Voyager 1 Pale Blue Dot image of Earth that we took from beyond the orbit of Neptune. Another was to process images, when we could, in natural color. I took it as my responsibility to release to the public image products that would convey what the scene would look like, in color and configuration, if we were actually there. It was extra work for sure, but I gladly committed myself to it.

And that’s how Cassini became the first planetary mission on which processing images in colors as true to natural as possible, and creating a color-consistent body of work, became ‘a thing’.

To produce natural color requires an accurately calibrated image production pipeline. We had insufficient funding prior to launch to do a complete job at this important task. Even if we had the funds, we still needed to do calibration in flight so that we would know how the imaging system’s response to in-flight conditions changed over time. And it did change. Calibration of our cameras, as it turned out, would be ongoing throughout, and up to the end of, the mission.

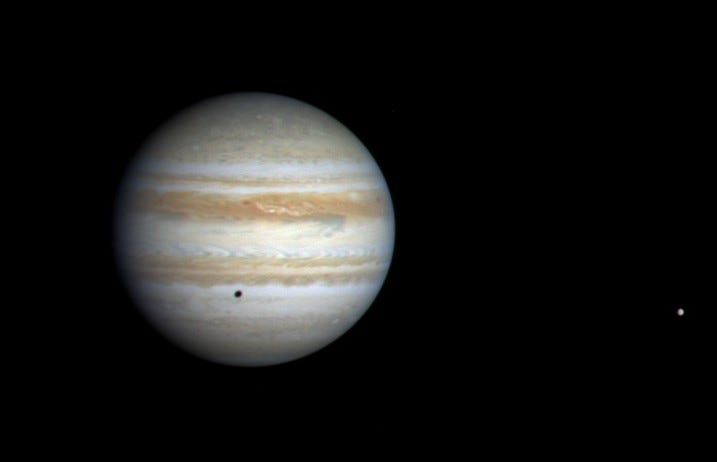

Our calibration software wasn’t ready yet during Jupiter flyby so I sought the advice of amateur astronomers as to what the color of Jupiter should be. The most prominent color was a brick orange/red. Cassini’s first color image, created at CICLOPS, was of Jupiter and its moon Europa, taken on October 4, 2000 as we started our official approach to Jupiter.

Caption: Cassini’s first color image, of Jupiter and its moon Europa, was released on October 9, 2000, John Lennon’s 60th birthday. Europa’s shadow is seen on the planet.

I very much wanted to publicly release the image on October 9, John Lennon’s 60th birthday. It would be my tribute to him. I had to sweet talk the public affairs people at JPL and NASA Headquarters in Washington D.C. into letting me release it on that day. I was delighted that they agreed.

I don’t remember now why, in the early days of our time at Saturn, the ring colors and some regions of the Saturn atmosphere turned out pinkish. I know our calibration procedure was not yet very accurate, and towards the end of the mission, the colors became more beige and somewhat muddied. They also could change depending on the illumination and viewing conditions, which was expected. That the uncertainties in our calibration process early on were large enough to accommodate color differences that would be perceptible to the human eye was another complication. In summary, achieving exact true color, though certainly a worthy goal, can be difficult even in the best of circumstances, and at this early stage in the mission, as we approached Saturn, we were somewhat winging it.

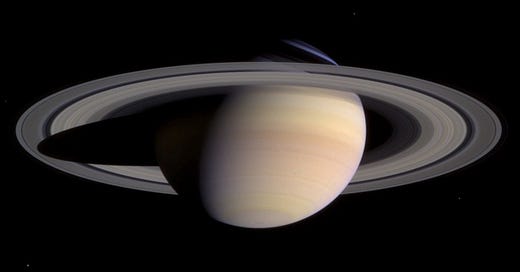

Caption: This color NAC image we took on ‘the last eyeful’ day of March 27, 2004 from a distance of 29.7 million miles from Saturn, is a composite of three exposures, one each in red, green, and blue spectral filters. The image scale is 178 miles per pixel.

However, color variations within our images were reliable. And variations in the colors of different atmospheric bands and features in the southern hemisphere of the planet, as well as subtle color differences across Saturn's middle B ring, were becoming more distinct the closer we got. Such variations generally imply different compositions, but under certain viewing conditions can indicate particles of different sizes. The nature and causes of the color differences in both the atmosphere and the rings were major questions to be investigated by Cassini scientists during the mission and each objective was pursued in depth as the mission progressed.

About the image itself … the bright blue sliver of light in the northern hemisphere is sunlight passing through the Cassini Division, the noticeable gap in Saturn's rings, and scattered by the cloud-free upper atmosphere. We hadn’t seen any blue on Saturn during the two Voyager encounters and it caught the imaging team scientists completely off guard. I will leave the mysterious blue on Saturn to a future episode of this newsletter. Or maybe my book. We’ll see.

The moons visible in the image are (clockwise from top right): Enceladus (313 miles across), Mimas (246 miles across), Tethys (660 miles across), and Epimetheus (70 miles across). Epimetheus is dim and appears just above the left edge of the rings. Brightnesses have been exaggerated to aid visibility.

Also in the image above, two faint dark spots are visible in the southern Saturn hemisphere. These spots are close to the latitude where Cassini had earlier seen two different storms merging in mid-March 2004.

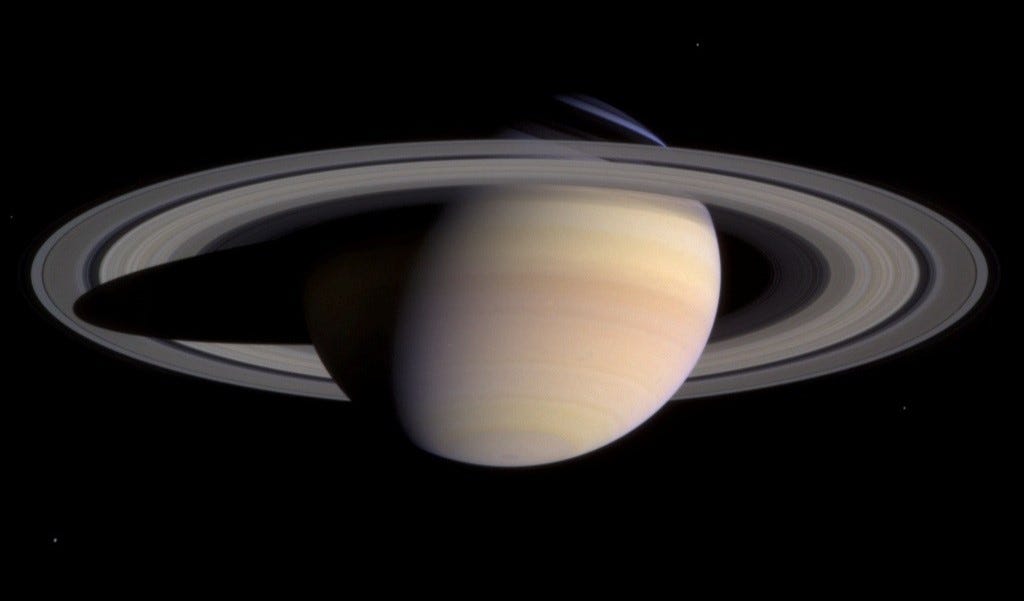

Caption: A month and a half into its long approach to Saturn, the Cassini spacecraft captured two storms, different than the ones in the color image above, each a swirling mass of clouds and gas, in the act of merging.

There is a fascinating and very scientifically gratifying story regarding the provenance of such storms, and how they relate to the underlying structure of Saturn’s interior. That story too will be left for the future. Stay tuned!

I am so happy you are doing this. I loved watching along with the mission and sharing it with my students. Thank you.

Thank you for sharing, really nice to read some of the insights into the program