April 16, 2024

Dear Friends,

Twenty years ago today was a day that we on Cassini, and especially those of us on the imaging team, had eagerly awaited ever since our mission to Saturn had been officially started, the science teams had been formed, and we had all set about designing and building the scientific instruments we would fly to Saturn.

Though Titan was discovered in 1655 by Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens, it wasn’t until 1944 that it was found by another Dutch astronomer, Gerard Kuiper, working in the US, that Titan had an atmosphere. Kuiper deduced this after he recognized a feature in the visible spectrum of the moon’s reflected sunlight at a wavelength of 619nm where the molecule methane had a strong absorption. This was the first detection of an atmosphere on a satellite, and the presence in Titan’s atmosphere of methane – a molecule with one carbon and four hydrogen atoms –came as a great surprise. Upon his discovery, Kuiper said, “It is of special interest that this atmosphere contains gases that are rich in hydrogen atoms; such gases had previously been associated with bodies having a large surface gravity." He was referring to the detection of methane on Jupiter in the 1930s and his expectation that a small body like Titan would be incapable of retaining such a light molecule.

Methane is one of the simplest organic materials and its presence on Titan eventually gave rise to some public speculation that there might be creatures living on the moon’s surface. Scientists may not have taken such notions seriously, but nonetheless, for those of us who were present at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory the day in late 1980 that Voyager 1 flew by Titan, the suspense in waiting for those first images of Titan was intense and exciting.

Sadly, what Voyager found was a moon enshrouded in a thick globe-enveloping orange haze that scattered visible light so strongly the cameras were unable to see the surface. However, other instrument science teams were successful in revealing the near-surface environmental conditions and their reports were astonishing: A pressure 50% greater than that on Earth and a temperature around 300 degrees Fahrenheit below zero. Under such conditions, methane would be near its triple point, as water is here on Earth. That meant it could take the form of a gas, liquid, or a solid, depending on how far the conditions at any locale, on the surface or in the atmosphere, deviated from the triple point. Here was a moon with an atmosphere hosting a substance that could in principle do on Titan everything that water can do here on the Earth: form bedrock, rain from the skies, collect to become rivers and cataracts, carve channels, fill low lying basins, evaporate into clouds, and so on. Voyager may have left behind no tremendous images of Titan’s surface, but what it did leave was solid justification to return to Saturn in the future to try again.

In the years following the Voyager Saturn encounters, our understanding of the Titan environment took two big leaps. Based on the Voyager results, it was predicted that the near-surface temperature was cold enough and there was likely sufficient methane on Titan to cover the entire surface with liquid hydrocarbons. A global methane ocean. Wow! Straight out of science fiction.

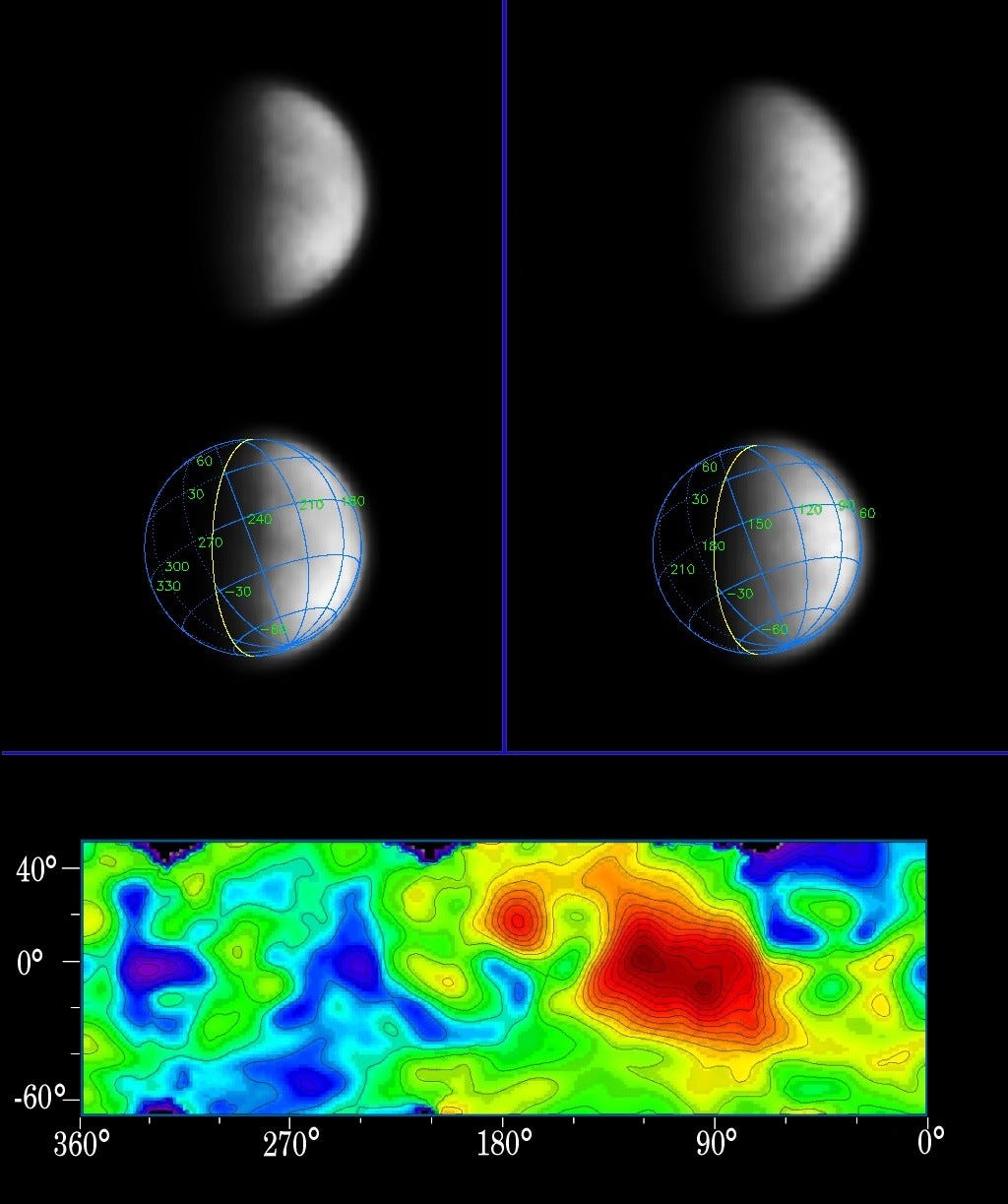

It had also been found by ground-based astronomers that it was indeed possible to see down to the surface of Titan if you knew where to look. The spectrum of Titan, from the orange region to the near-infrared wavelength limit of our cameras – ie, outside the region where Voyager was able to see -- was dominated by strong methane absorption bands. If you looked in these narrow bands of the spectrum only, the surface would be invisible because methane would absorb any sunlight in those bands that fell on the moon and no signal would ever make it out. But instead, if you looked at wavelengths in between the methane bands, where methane wouldn’t be a problem, in principle you could see the surface. In these spectral windows, the only thing that might produce poor visibility would be the haze in the atmosphere, and the ground-based astronomers examining Titan had found if you looked in those windows falling in the red and near-infrared, haze scattering was reduced and the surface could in fact be seen. This was proven decisively when the near-infrared camera on the Hubble Space Telescope was used to produce a map of features on Titan’s surface looking in such a window. (See figure caption below.)

It became obvious to my team and me that we needed to carry narrow-band filters that could accept light from each of the 3 inter-methane band windows through which our cameras were able to see. And for good measure, we would also carry polarizing filters that could work in tandem with the inter-methane filters to decrease scattering even more.

Also, as part of our Titan observing campaign, we sought out those times in the mission when we would be looking at Titan under optimum viewing conditions: ie, close to full illumination, with the sun at our backs, and looking as close as we could to ‘directly down’ on the surface in order to decrease the path length and, therefore, scattering through the atmosphere.

By the time launch day, October 15, 1997, had arrived and we bid our cameras farewell, we knew we were sending to Saturn an imaging system as ideally equipped as anyone could possibly build to investigate, at close range, the largest, continuous piece of real estate in our solar system that still had not been seen by human eyes.

And when the day finally came, 7 years later, that we learned our filter strategizing had worked and we were seeing the surface of Titan for the first time, it was like being called to report for duty on the greatest exploration of all time. We knew then there would be extraordinary sights and victorious moments in our future.

On that day, I recorded in my Captain’s Log how the moment struck me. This is what I wrote.

The Veils of Titan

Today, we have reached a turning point in our travels on approach to the ringed planet.

We have at last glimpsed the surface of the fabled world Titan, Saturn's largest moon and the greatest single expanse of unexplored territory remaining in the Solar System today. What wondrous sights now await us on this remarkable journey we can only imagine.

Titan has long intrigued those who watch the planets. It is a Mercury-sized icy body whose surface environment may be, in some respects, more like Earth's than any other in the Solar System. Like Earth's, its atmosphere is thick and largely molecular nitrogen. Unlike Earth's, it is lacking free oxygen and is suffused with small but …

Caption: Two images of Titan taken with the narrow angle camera through a filter designed to look through the inter-methane-band window at 938nm. The image on the left was taken 4 days after the image on the right. Between the 2 views, Titan had rotated about 95 degrees. The images have been magnified 10x using a procedure which smoothly interpolates between pixels to create intermediate pixel values. They have been enhanced in contrast to bring out details. The original image scale is 143 miles/pixel. It was noteworthy that the surface was visible to Cassini from this approach geometry which was not the most favorable for surface viewing. The map shown was constructed from images taken by the Near Infrared Camera (NICMOS) on HST (Meier et al., Icarus 145, 462, 2000). The blue and green are the darkest areas; yellow and red are the brightest. The brightest, red region in the map was named Xanadu. We can see Xanadu in the Cassini image on the right. But at this point in the mission, we did not know what Xanadu or any other feature on Titan actually was.

… significant amounts of gaseous methane, ethane, propane, and other simple and not-so-simple organic materials containing hydrogen and carbon. Some of these compounds, methane and ethane, may be liquid at the surface, despite the unimaginable cold of -300 degrees Fahrenheit. And though there is no liquid water, what water does on Earth, methane does on Titan. The presence of this simple hydrocarbon as a liquid on the surface and a gas in the atmosphere gives Titan a terrestrial-like greenhouse cycle and a boost in temperature, warming its lower atmosphere. If present-day Titan could be warmed enough to melt its icy exterior, its atmosphere would bear a striking resemblance to that of early Earth, billions of years ago, prior to the emergence of life. Might Titan be a frozen, pre-biotic Earth, telling a tale littered with clues to the origins of terrestrial life long ago?

Despite the Voyager explorations of the early 1980s, the details of Titan's story remain unknown, hidden beneath an atmosphere impenetrable to the Voyager cameras. At the moment, what lies on its surface exists only in the mind's eye.

And in the mind's eye, it is a strange place indeed.

Patchy methane clouds float several miles above the icy ground. In places, large, slow-moving droplets of methane mixed with other liquid organics fall to the surface in cold but gentle rains, cutting gullies, forming rivers and cataracts, carving canyons, and filling basins, craters and other surface depressions. Imagine Lake Michigan brimming with paint thinner.

Above the methane clouds and rain lies two hundred kilometers worth of globe-enveloping red smog, making the Titan nights starless and the days eerie dark, where high noon is as dim as deep Earth twilight. Over eons, smog particles have drifted downwards, growing as they fell, to coat the surface in a blanket of organic matter. On high, steep slopes, methane rains have washed away this sludge, revealing the bright bedrock of ice. Could Xanadu, the brightest feature on Titan, be a high, methane-washed, mountain range of ice?

Occasional bolts of lightning momentarily brighten the gloomy landscape, and wind-blown waves lap the shores of hydrocarbon lakes and seas dotting the scene.

This is a rich and complex environment, where oddly familiar terrain is carved by odd and unfamiliar substances ... a fascinating, virgin world whose only rival may be the Earth itself, with sights still unseen by human eyes.

Anticipation is at its greatest. The pulse quickens, the mind races, the soul is grateful. It is a singular privilege to be standing on the threshold separating ignorance and knowing.

And that's exactly where we are.

This is exploration at its finest and is precisely why we have come to this strange and far-away place.

Step aside, Captain Kirk. This one belongs to us.

— Carolyn Porco, Cassini Imaging Team Leader

Thanks for bringing Titan to life for us! I love its secrecy, alien composition, and the nomenclature of the moon's geological points. Here's a slam-style poem inspired by it...

KRAKEN MARE

collar the kraken.

hear her holler.

put your back into holding her down,

folding her crown under secrecy’s haze.

obscured to the gaze,

the dragon be drowned in a methane lake.

you’ll never be found 'cause you’ll never awake―

opaque to your fate hackin the ground.

cover the mar in hideaway mounds.

the ring’s hollow sound haunting the grave.

too late to escape titan’s guilt as it pounds

what you lack in the good-come-around.

a monster probed by the foolishly brave,

snackin on clowns to stay hidden from fame.

let her lie―

the kraken wound round your name.

How cool is that?

And you have Sagan's talent for writing. Please, never stop amazing us!